Introduction

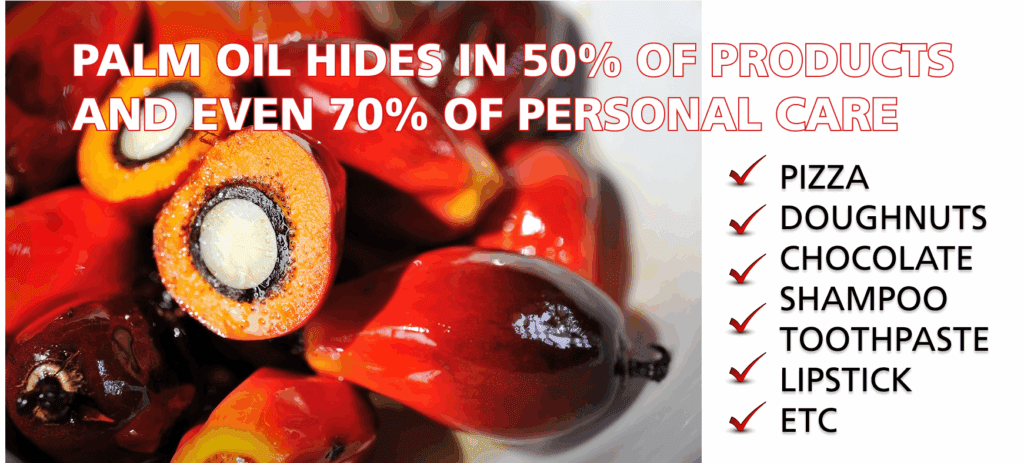

Palm oil and tigers are locked in a brutal war for survival. Palm oil is the cheapest and most consumed vegetable oil on earth, found in more than half the products on supermarket shelves—biscuits, margarine, instant noodles, cosmetics, shampoo, even biofuels. Malaysia and Indonesia, especially the island of Sumatra, dominate this market. Together they supply over 85 percent of the world’s palm oil. For governments, this is called economic success. For tigers, it is a death sentence.

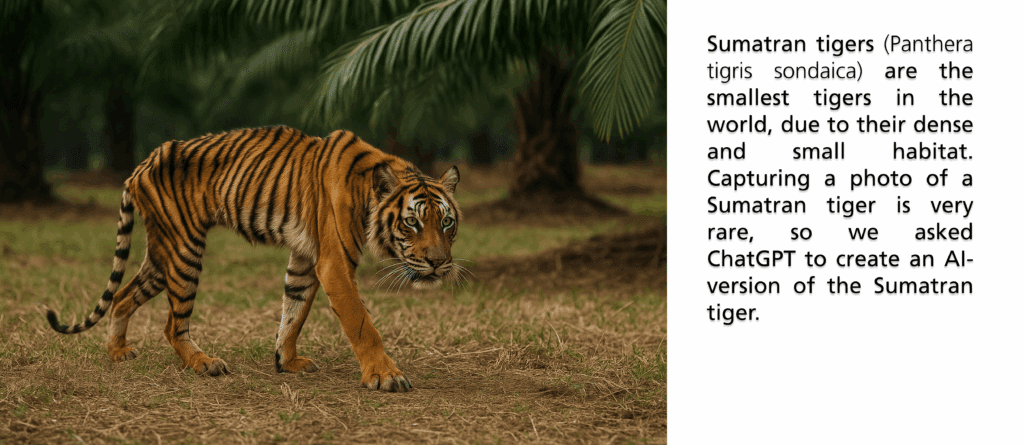

The Malayan tiger clings to survival with fewer than 150 left in the wild. The Sumatran tiger’s population hovers around 400. Both subspecies are being strangled by palm oil plantations that bulldoze rainforests, erase corridors, and set fires that choke skies across Southeast Asia. These monocultures leave no room for wildlife. Prey vanishes, water systems collapse, and predators wander into villages where they are poisoned, electrocuted, or trapped.

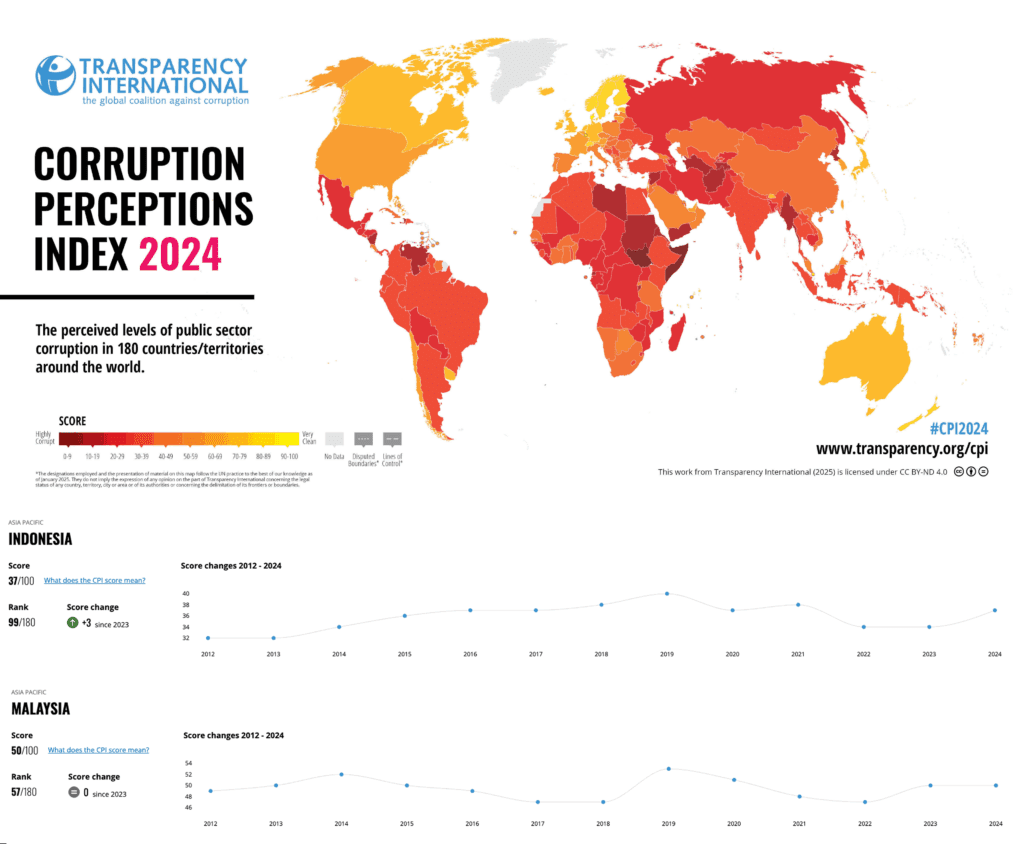

Governments in Malaysia and Indonesia hail palm oil as national pride. Corporations wrap it in “sustainability” labels. Banks keep the money flowing. But behind this polished story lies systemic corruption, forest destruction, and tiger extinction. Palm oil and tigers cannot coexist—and the only force slowing destruction is outside pressure: NGOs, activists, journalists, and sometimes diplomatic threats.

What is Palm Oil?

Palm oil comes from the fruit of the oil palm tree, native to Africa but industrialized in Southeast Asia. It is cheap to produce, extremely versatile, and has the highest yield of any vegetable oil. On a global market obsessed with profit margins, that combination made palm oil unstoppable.

Today it is the invisible ingredient in over 50 percent of supermarket goods. Snacks, sauces, chocolates, instant ramen, detergents, ice cream, soaps, and cosmetics are all tied to palm oil. Even so-called “green energy” biofuels rely on it. By 2025, Malaysia and Indonesia together produce over 70 million tonnes annually.

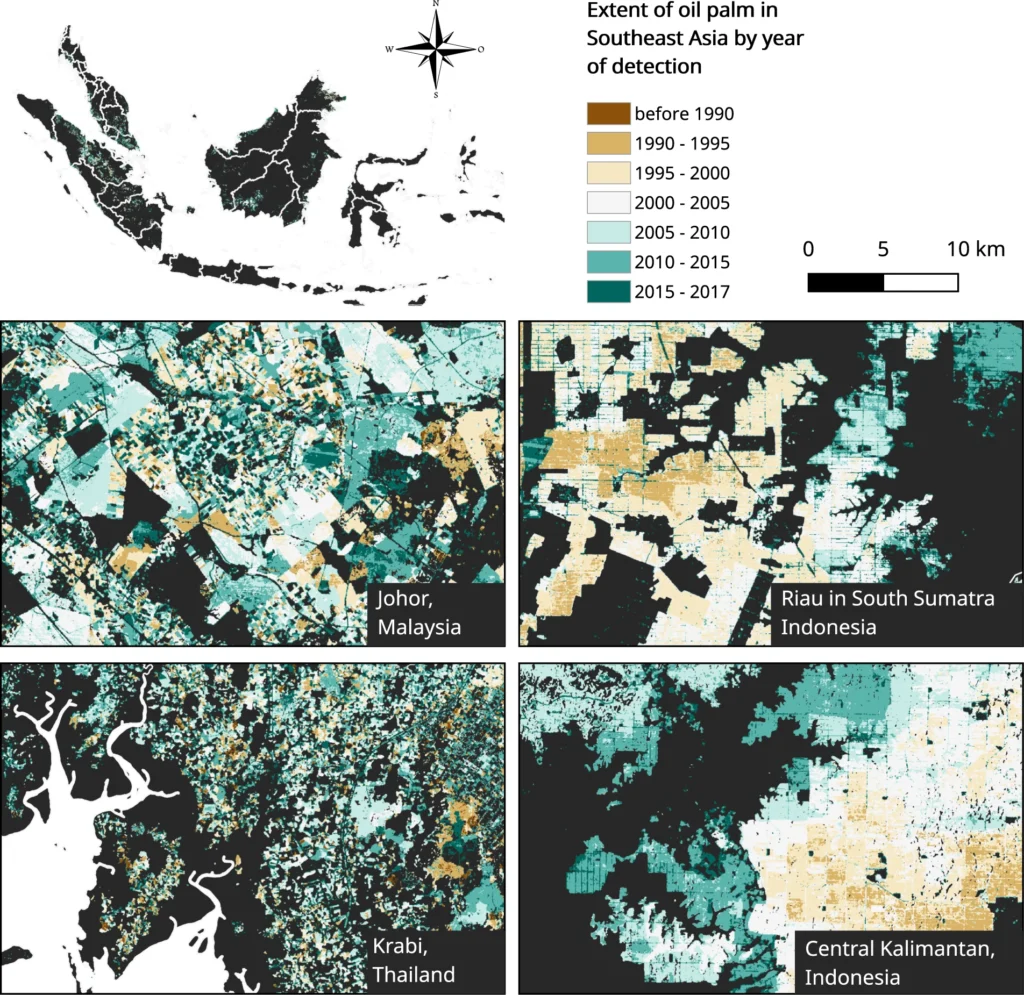

The scale of this expansion is staggering. Where rainforests once stretched unbroken across Sumatra and peninsular Malaysia, seas of monoculture palms now dominate the landscape. The transformation has been so rapid that in just four decades, entire ecosystems have been re-engineered for global demand.

The result is not only biodiversity collapse but a corridor crisis for tigers. These apex predators require vast territories, crossing landscapes that plantations erase. What is advertised as progress in trade statistics is, for tigers, the map of extinction.

Palm Oil and Tiger Habitat Loss

The first and most devastating impact of palm oil on tigers is habitat destruction.

In Sumatra, the island’s lowland forests are shredded by concessions. Provinces like Riau, Jambi, and Aceh are carved apart by plantations that should never have been allowed under conservation law. Even the globally significant Leuser Ecosystem—one of Earth’s last places where tigers, elephants, rhinos, and orangutans coexist—has been repeatedly targeted by palm oil firms. Companies slash forests with bulldozers and then torch what remains. The result is an endless cycle of haze, toxic air, soil erosion, and silenced forests.

In Malaysia, plantations spread through Pahang, Johor, and Terengganu, eating into critical Malayan tiger habitats. Lowland rainforests are converted to cash crops. Corridors vanish. Tigers that once roamed between Taman Negara and surrounding forests are now trapped in shrinking patches, too small to sustain viable populations.

Officials call this “balanced development.” But NGO satellite mapping tells a different story: the bulldozers are relentless. Without watchdogs documenting forest loss, many of these plantations would remain invisible to the public. The habitat collapse is not an accident. It is deliberate policy, and tigers pay the price. Palm oil and tigers are just not a good match.

Palm Oil and Human–Tiger Conflict

As palm oil plantations spread, tigers are forced into landscapes where they do not belong. With forests bulldozed and prey animals disappearing, tigers are pushed onto the edges of plantations, villages, and farms. In Sumatra, workers often stumble upon tigers moving through rows of palm. Fear takes over, and the response is almost always violent: wire snares set around the plantation, poisoned bait near work sites, or crude electrocution fences wired to kill anything that touches them. These are not isolated cases but part of daily survival strategies for communities living on the frontlines of palm oil expansion.

In Malaysia, the pattern repeats. Displaced Malayan tigers approach villages where cattle and goats are penned. Livestock killings quickly lead to retaliatory hunts. Local newspapers report these as “human–tiger conflicts,” shifting blame onto the animal. But this is not conflict—it is forced displacement. Tigers have no choice but to step into human-dominated areas once their forests are erased. The real culprit is not the tiger but the palm oil plantation that destroyed its hunting grounds.

Corruption and the Palm Oil Industry

Palm oil thrives because of political corruption. In Indonesia, illegal permits are issued for plantations inside supposedly protected forests. Local officials profit directly through land concessions or quietly take bribes to look the other way. In Malaysia, political elites are deeply enmeshed in the palm oil sector, holding stakes in major plantation companies or using it to build patronage networks. On paper, laws exist to regulate deforestation. In practice, enforcement is weak, inconsistent, or absent entirely.

International finance keeps the machine running. Western banks, Asian lenders, and global investment funds continue to pour billions into palm oil giants. Certification systems like the “Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil” (RSPO) provide a greenwashed label of approval that calms consumers but changes nothing on the ground. Bulldozers keep clearing, fires keep burning, tigers keep dying. Again: palm oil and tigers are not a good match, to say at the least.

Here, social pressure matters. NGO investigations, activist protests, and investigative journalism are the only forces that expose this corruption. Diplomatic pressure from trading partners, such as the EU’s deforestation-linked import bans, rattles palm oil lobbies more than any local regulation. Without that outside push, the plantation industry operates with impunity.

Palm Oil and the Poaching Nexus

Plantations do not just erase forests—they provide free infrastructure for poachers. Every plantation requires roads for trucks and laborers. These roads slice deep into tiger country and become highways for traffickers. Hunters use them to carry in wire snares, firearms, and poison. The same trucks that haul palm fruit can smuggle tiger skins, bones, and other wildlife products out.

In many cases, plantation workers themselves participate in poaching, either for income or out of resentment toward displaced predators. Company security forces are often complicit, turning a blind eye or profiting from trafficking networks. Some plantations have been directly linked to organized crime syndicates that use palm operations as a cover.

Again, it is NGOs, activists, and journalists who expose these networks. Without undercover investigations and public reports, the palm-poaching nexus would remain invisible. When governments claim plantations and wildlife can coexist, they ignore this brutal reality: palm oil roads are also poacher roads, and every new concession makes it easier to kill tigers. Palm oil and tigers are on the opposite sides of the spectrum.

Case Study: Sumatra

The Sumatran tiger is the last surviving island tiger subspecies, uniquely adapted to dense rainforests and steep terrain. Yet fewer than 400 remain, clinging to isolated patches of forest surrounded by palm oil plantations. Provinces like Riau, Jambi, and Aceh have become ground zero for deforestation, with bulldozers erasing tiger corridors at alarming speed. Roads for palm transport cut into Kerinci Seblat, one of Sumatra’s largest national parks. The Bukit Tigapuluh forest, once celebrated as a stronghold for tigers and elephants, is now reduced to fragmented blocks of trees surrounded by seas of palm. Palm oil and tigers: yet again, not a good match.

Local communities live on the margins of these concessions. Some are trapped as plantation laborers, earning wages too low to break cycles of poverty. Others resort to bushmeat hunting or poaching, feeding the demand for tiger skins and bones. For them, survival is tied to exploitation. But the structural blame lies higher: corporations hungry for expansion and politicians profiting from concessions.

NGOs working in Sumatra have shown how illegal palm concessions overlap directly with tiger habitat. Investigative journalists have uncovered bribery networks granting permits in “protected” zones. Without these exposures, the destruction would remain hidden behind trade statistics.

Case Study: Malaysia

The Malayan tiger is in even deeper crisis. Once ranging across peninsular Malaysia, it now survives in tiny, disconnected populations. Fewer than 150 remain. Palm oil plantations are central to this collapse. In states like Pahang, Johor, and Kelantan, lowland rainforests—prime tiger habitat—have been converted into plantations and highways funded by palm revenue. These projects sever critical corridors linking reserves such as Taman Negara, Belum-Temengor, and Endau-Rompin. Tigers trapped in these fragments cannot maintain genetic diversity or stable prey populations.

Conflict has escalated. Displaced tigers sometimes prey on livestock. Villagers retaliate with poison, traps, or rifles. Officials call it conflict, but the true cause is displacement by palm oil. Poachers from neighboring countries exploit plantation roads, pushing the species further toward extinction.

Here too, exposure comes from outside pressure. NGOs like MYCAT and international media have drawn attention to the Malayan tiger crisis, linking it directly to palm oil expansion. Diplomats raise the issue quietly in trade talks, though rarely with enough force. Without social and diplomatic pressure, the Malayan tiger will vanish in a generation. Or even sooner, as Malayan palm oil and tigers are not to be united with each other.

Global Responsibility

Palm oil’s devastation is not only a Malaysian or Indonesian problem. It is global. Every consumer who buys biscuits, chocolate, shampoo, or packaged noodles is connected to this destruction. Multinational corporations—Nestlé, Unilever, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble—rely heavily on palm oil. Banks and investment funds in New York, London, and Singapore finance the expansion. Supermarkets stock their shelves with products that hide palm oil behind vague labels like “vegetable oil.”

Governments in Southeast Asia defend the industry as economic lifeblood. But global demand is what sustains it. Without international consumption, the industry collapses. This means global responsibility is unavoidable. Pressure works. Consumer boycotts and NGO campaigns have forced some companies to reform. Investigative journalism exposing illegal palm operations has rattled corporate boardrooms. Diplomatic moves, like the EU’s deforestation-linked import bans, have made palm oil lobbies nervous.

But the scale of reform still lags far behind the scale of destruction. Tigers in Malaysia and Sumatra cannot wait for corporate pledges. They need forests intact today, not promises of “sustainability” tomorrow. Global demand must be held accountable.

What Must Change in Malaysia and Sumatra

The link between palm oil and tigers is not inevitable. It is the result of choices—corporate greed, political corruption, consumer demand, and global indifference. If those choices can be made, they can also be unmade. But solutions require pressure, transparency, and enforcement.

First, enforce zero-deforestation laws in Malaysia and Indonesia. Protected areas cannot continue to be carved up with concessions. Illegal plantations must be dismantled, and the companies behind them prosecuted rather than protected. Diplomatic leverage is critical here: when the European Union tied imports to deforestation standards, plantation owners lobbied aggressively against it. Pressure works. The threat of lost markets frightens the industry more than local fines.

Second, protect tiger corridors instead of replacing them with token “eco-tourism” projects. Tigers need vast, connected forests, not isolated reserves cut off by monoculture. Governments must prioritize corridor restoration and stop highway and plantation projects that block tiger movements.

Third, support alternative livelihoods for communities. Plantation workers and smallholders are trapped in cycles of poverty, often forced into labor or complicit in poaching. Programs that provide real alternatives—sustainable farming, tourism linked to living forests, or fair-trade initiatives—are essential if pressure is to reach beyond corporations.

Fourth, demand palm-free alternatives in global markets. Supermarkets and consumer brands must be forced to stop hiding palm oil behind “vegetable oil” labels. Palm oil that comes from deforestation must be banned from international markets. Consumers hold power when guided by transparency.

Also, build social pressure. NGOs, activist groups, and investigative journalists are the only forces that consistently expose palm oil’s corruption and complicity in tiger deaths. Protests, boycotts, shareholder revolts, and viral campaigns keep the industry under scrutiny. Plantation owners and politicians fear public exposure more than local law. The role of independent journalism is equally vital: it uncovers the permits granted in secret, the bribes exchanged, the tiger deaths covered up. Without this spotlight, destruction continues unseen.

And last, the palm oil industry must be held accountable for everything it has destroyed in the pursuit of profit. For decades, corporations and their political allies have sacrificed forests, wildlife, and local communities for the sake of swollen balance sheets. The billions of dollars generated from this destruction cannot remain locked away in boardrooms and foreign bank accounts. That money belongs to the forests that were burned, the rivers that were poisoned, the communities that were displaced, and the tigers that were driven to the edge of extinction.

Reparations are not optional—they are essential. Profits carved out of tiger habitat must be reinvested into protecting and restoring that same habitat. If palm oil has any future beyond blood-soaked profits, it must pay back the ecological debt it owes. Only then, if ever, could palm oil and tigers coexist—not as enemies in a war for land, but as reluctant partners in survival.

Palm oil thrives on silence. Social, diplomatic, and media pressure must keep breaking that silence until action becomes unavoidable.

Outro: Malayan and Sumatran Tigers go Extinct Within a Decade, Unless Something Seriously Changes

Palm oil and tigers cannot share the same future. In Malaysia and Sumatra, plantations are driving Malayan and Sumatran tigers toward extinction. Every hectare cleared erases another corridor. Every concession approved signs another death warrant.

Governments praise palm oil as progress. Corporations wrap it in “sustainability.” Banks profit quietly. And on the ground, forests burn, poachers strike, and tiger carcasses are carried out in silence.

But cracks are appearing. Activists demand accountability. NGOs map illegal concessions and name the companies behind them. Investigative journalists risk intimidation to reveal corruption. Diplomatic pressure is forcing discussions on trade bans tied to deforestation. Each of these actions shows one truth: pressure works.

If global demand continues unchecked, Malayan and Sumatran tigers will vanish within decades. If the world acts—truly acts—by exposing corruption, enforcing zero-deforestation, supporting communities, and cutting palm oil’s lifelines, survival is still possible.

The question is no longer technical—it is moral. Do we choose cheap biscuits and soaps, or do we choose wild tigers? Palm oil and tigers cannot coexist. The decision is ours. As palm oil and tigers will never have a joint future.